Project Description

My second interview with DreamWorks Animation

Published: April 19, 2015

If you’re tired of reading DreamWorks stuff on my blog, you should skip this post. I understand your fatigue, but I still have a few things I want to write about that place. DreamWorks was a big part of my life last year, and I want to share that part of my life with whoever wants to learn.

If you’re not tired of reading DreamWorks stuff on my blog, then boy do I have a treat for you!

Buckle up. This is a long one.

I wrote a post back in October 2013 about my first interview with DreamWorks. They were visiting campus looking for new technical director talent. My interview did not go as well as I wanted it to, but through that kinda awkward experience, I met Mark, Tiffany, and Laurie, who ended up being among the most important contacts I made during my tour at Penn.

Four months after my first interview, I got a call from Tiffany, and learned the DreamWorks internship program was going to include technical director interns. Tiffany wanted to know if I wanted to be considered for the position. Yes. My answer was yes. An outrageously overeager yes first, followed quickly by a few less manic yeses.

Advice part one. Take advantage of career fairs, on-campus interviews, and company-hosted events. Participate wherever you can, even if you don’t feel qualified yet. Introduce yourself to everyone. Try to build relationships. The people you meet at those events are the same people who can help you survive the hiring process.

The only reason I got that call from Tiffany in February was because I made myself known to her in October. She had my resume. I got my chance. When applying for jobs, the first gatekeeper isn’t your recruiter. It’s not the person on the other end of your phone screen either. It’s the software that filters and discards your application. Building a relationship with a real person is the most reliable way to get your name on the short list of serious candidates.

This post is about the interview I had as a result of Tiffany reaching out to me–my second interview with DreamWorks Animation and probably the most important interview I had during my first 23 years of life.

The setup

Since DreamWorks’ U.S. operations are based in California and I was living in Philadelphia at the time, my interview took place over a video conference call. Thankfully, I didn’t have to set anything up. The career services center at Penn took care of the logistics. I just had to bring my brain to my assigned room at my assigned time.

I liked the idea of a video interview. If I disappointed, the disappointment on my interviewers’ faces would be hidden in the pixels. At least, I hoped the disappointment would be hidden. Also, it’s easy to fake eye contact through a screen. Eye contact is hard and it feels weird sometimes. It feels weird most times.

My interview was 90 minutes long and broken up into 3 30-minute sections. During each section, I spoke with 2 technical directors at the same time. So, 6 total. Each section was designed to cover different material. My first section covered “oddball” questions (brain teasers). My second section covered technical material. And my third section was filled with open-ended questions meant to test my communication skills.

Advice part two. If you want to know more about your interview before you take the hot seat, all you have to do is ask. Your recruiter will fill you in on everything you need to know. Sometimes, they’ll even give you a short list of recommended topics to brush up on beforehand. No one wants you to be surprised during your interview, least of all your recruiter. In fact, there are few people who want you to succeed more than your recruiter does. If you perform well enough during your interviews to get hired, then your recruiter can cross the open position you just filled off their to-do list. A win for you is a win for everyone–you, your recruiter, the company. No one is conspiring against you.

I’m thankful I asked Tiffany what kinds of questions to expect. I wouldn’t have known to practice solving brain teasers otherwise.

The storm before the storm

Have I mentioned how stressed I was about this interview yet? Because the days leading up to it were the most stressful in my entire life. I couldn’t think about anything else. I started sleeping less. I started eating less. I stopped paying attention to my classes. Instead, I tried to cram every computer science fact, graphics algorithm, and brain teaser I had ever learned into the front of my brain. It was destructive behavior. Part of me knew my actions weren’t helping, but I couldn’t stop. The interview felt too high stakes to stop. I saw this interview as my only chance to get into the animation industry.

Before grad school, I spent six years submitting resumes to animation companies. In those six years, I didn’t hear back from anyone. Now, I had an interview with an animation studio on the calendar! Awesome! But what if I screw it up? What if I don’t get hired? Will it be another six years before I get another chance to prove myself? “Probably,” said my stupid brain. Then my stupid brain followed with, “Actually, this is probably the only chance you’re ever going to get.”

I felt like I had stumbled upon a giant fork in my life road. Interviewing well at the fork led to an internship at DreamWorks, and then further down the road, to a fulfilling career in feature animation. Interviewing poorly at the fork led to none of those things. As far as I could tell, that path led to a life of sadness.

This sounds shortsighted. It was shortsighted. It’s unlikely that bombing one interview would have ruined my life forever. But that’s how I felt, and I was incapable of controlling those feelings. Even knowing what I know now about the industry, if I were to go back in time to this interview, I think I’d feel the same. I think I’d freak out all over again.

I wish I could tell you to take it easy and to not freak out about your interviews. I can’t. Some experiences will fundamentally change the course your life takes. They will change who you are and who you become as a person. Jobs are often those experiences. One bad interview can lock you out of those experiences. For me, this DreamWorks interview led to a formative internship, and that internship led to a full-time gig with Blue Sky. Had I not performed well during this interview, I don’t think I’d be working in the animation industry at all today. I’m not sure where I’d be.

So, yeah. I was really stressed.

The questions – Oddball

One. How would you count all the grains of sand on a California beach without the use of sophisticated tools? (Start small. You can estimate the number of grains in a cubic centimeter easily by hand. Build on that knowledge.)

Two. You have a drawer with 12 white socks and 12 red socks. The power is out in your room. How many socks would you have to pull out of your drawer to guarantee a match is made? How many socks would you have to pull out to guarantee two matches? What is the formula for matching any number of pairs of socks? (Solve for the worst case at each step.)

Three. There are three boxes. One with all red balls. One with all blue balls. One with red and blue balls mixed. All three boxes are mislabeled. Can you properly label all the boxes after only drawing a single ball? How? (You have to draw from the box labeled “mixed” if you want the information learned to be unambiguous.)

Four. You have eight coins. One coin is counterfeit and is heavier than the other seven, which all weigh the same. You have a balance scale. How can you identify the counterfeit coin using the scale only twice? (Fight the urge to divide the coins into two even piles at the start.)

Five. Given the Fibonacci number sequence and the sequence of prime numbers, which one grows faster? (Work out the first few cases in your head. The solution quickly becomes obvious.)

When answering these questions, start small and think out loud. It’s not important how quickly you get to the correct answer. What’s important is how you arrive at the correct answer. Sometimes, there is no correct answer. In those cases, what’s important is how you arrive at a reasonable answer.

The questions – Technical

One. Explain the model, view, controller paradigm to us. (Asked because I had iOS projects listed on my resume.)

Two. What is unit testing and what are its limitations?

Three. What are the differences between interfaces and abstract base classes?

Four. What scripting languages do you know? (I had played with Perl and Python some. My resume implied I knew them better than I did. This could have bit me in the ass. Luckily, we didn’t do a deep dive into scripting languages.)

Five. What is your favorite programming language and why? (C++, because it was the only language I could talk about semi-intelligently at the time.)

Six. How does Maya’s Dependency Graph architecture work? (Asked because I had a Maya plugin project listed on my resume.)

Technical questions usually get pulled straight from your resume. If you claim to know C++ on your resume, then you should expect to get asked some C++ stuff during your interviews. Inflating your knowledge on your resume will probably bite you in the ass, but it might also help you land an interview in the first place, which gives you a chance to prove yourself in-person. It’s a balancing act. Outright lying on your resume is something I’ll never condone.

The questions – “Let’s just talk”

One. Teach us something. (For some reason, I talked about deadlifting–an exercise I still barely know how to do.)

Two. What’s your favorite animated movie and why? It doesn’t have to be a DreamWorks movie. (I really love The Incredibles.)

Three. Tell us about another movie you like that is not animated. (I talked about The Act of Killing because it was fresh in my mind. The Act of Killing is a super bummer to talk about, and I don’t recommend bringing it up in the middle of a lighthearted interview.)

Four. Explain the development process of an animated film. (Basically, what does a production pipeline look like?)

Five. Why do you want to work at DreamWorks?

Six. How would you handle being assigned many different high priority tasks simultaneously?

Advice part three. A lot of people believe questions like number two above are a trap.

It doesn’t have to be a DreamWorks film? So I can just start talking about a Disney or Blue Sky film right now, and you’ll be totally cool with it? No ill will? Yeah, right. I’m not falling for it.

In my experience, the people asking these questions really are totally cool with whatever answers you choose to give as long as you justify them. Talking about your real favorite films will always lead to more interesting conversations than talking about films you pretend to like. It’s easy to fake interest. It’s hard to fake the kinds of enthusiasm bred by passion.

I’ve been asked this question twice in the last year, once by DreamWorks people and once by Disney people, and I answered with The Incredibles both times. Answering honestly didn’t handicap me. It wasn’t a trap.

I feel the same way about the “What is your greatest weakness?” question. You can lie if you want to, but you’ll learn more about yourself if you tell the truth. I don’t recommend going overboard with self-criticism, but I don’t think it’s an interview death sentence to talk about legitimate weaknesses.

However, me choosing not to answer with a DreamWorks film didn’t mean I was unaware of DreamWorks’ legacy. Had I been asked during my interview to list every DreamWorks Animation release chronologically, including the Aardman films distributed by DreamWorks, I could have done it. I did my homework. Homework is important.

Mandatory interview prep for all positions always

The following questions are the most frequently asked (and most uninspired) interview questions known to (wo)man. You’ve probably been asked variations of these during your own interview adventures. You’ll probably be asked every one of them again during future interview adventures. These questions are easy to prepare for ahead of time, so there’s no reason anyone should ever stumble through them. I pulled these from one of Gayle McDowell’s books.

Challenges:

- Tell me about a challenge you’ve faced. How did you overcome it?

- Tell me about a setback you’ve faced. How did you handle it?

- Tell me about a difficult failure you’ve experienced.

- Tell me about a mistake you made. What happened, and what did you learn from it?

Influence/leadership:

- Tell me about a time when you influenced a team.

- Tell me about a time when you had to make a tough decision.

- Tell me about a time when you disagreed with someone.

Teamwork:

- Tell me about a challenging interaction with a team member.

- Tell me about a time when you had to build or motivate a team.

- If I called up your teammates, how do you think they would describe you?

Spend a few minutes answering these questions for yourself. Write your answers down. Every year or so, revisit your answers, and update them as needed. Even if you’re not actively interviewing, take the time to review and update your answers. It’ll seriously take you 15 minutes. If this exercise saves your ass during 1 interview, then it’s time well spent.

I keep my answers in Evernote. They’ve saved me more than once.

The Croods notes

I learned in my first interview with DreamWorks that deconstructing sequences, shots, or images in these kinds of interviews is common practice. In that first interview, I was asked which shot in How to Train Your Dragon I thought was the most complicated to achieve on a technical level and why. My answer was a rambling mess that revolved mostly around how hard I thought it must have been to make Toothless behave like a cat. What? It was bad. I was only half a semester into graphics stuff at the time, and my vocabulary for answering those kinds of questions was severely lacking. I didn’t know what to look for.

By the time this second interview rolled around, I had another full semester of graphics stuff under my belt, so my graphics vocabulary, while still not great, was much more expansive. Also, I knew what to expect, so I was able to prepare for it. The weekend before my interview, I watched The Croods and took notes on the things that seemed hard to do.

Before I go on, can we all agree that it’s really cool to be able to watch movies and call it interview preparation? Yes? Cool.

Here are some of the notes I took during that exercise.

Eep and the fireflies. The first shot where Eep, the film’s protagonist, comes into contact with fire gets my vote for most complicated shot in the entire film. It’s ~50 seconds long (I timed it), which is crazy long. For reference, the other shots in the film probably average 4-5 seconds each. Also, there are dozens of moving lights in this shot. This shot must have been a nightmare to render, and it was probably too expensive (in both time and resources) to render it more than once. Also, because there are so many interacting lights, any relighting that needed to happen probably had to be done by hand to look convincing, which means relighting probably wasn’t an option. This thing needed to be 99% correct before sending it off to the farm. 99% is a big ask.

The end of the world. Spoilers for The Croods I guess. This film is a lot about the world “ending”. All good world endings feature things exploding, and this film is no exception. There are a lot of explosions, which means a lot of destruction and fractured geometry and complex flow calculations to simulate dust and debris and a lot of volumetric rendering to capture the transmittance of light through thick dust clouds. That doesn’t sound easy.

There’s one “things exploding” shot that to me looked especially tricky to do. Grug, Eep’s dad, is in a cave, and the camera is looking out the cave’s opening. From the cave, you can see miles into the distance. In the distance, giant explosions start. Each successive explosion brings the destruction closer to the camera until fire and debris blow through the cave. One explosion seems hard. Many explosions layered on top of each other seems harder.

Since the virtual space this shot exists in is giant (miles long, remember?), I suspect a lot of what we see on screen are matte paintings. I’d be interested to learn how the effects department and matte painting department collaborated to make this shot happen.

Pink death birds. There’s a sequence where dozens (maybe hundreds) of pink death birds are flying around in a pack trying to eat our protagonists and such. I haven’t done much work with crowds, but they seem hard to do.

Crowd work generally requires procedural geometry and animation because modeling and animating 100+ background characters individually isn’t feasible. Procedural geometry means characters are created by mixing and matching parts from a geometry library. For instance, a simple geometry library for human characters might contain a dozen different pairs of legs, a dozen different torsos, a dozen different heads, and a dozen different hairdos. To procedurally model a character, one of each body part is randomly (or pseudorandomly) pulled from the library, scaled as necessary, and assembled.

For objects we’re familiar with, like people, the geometry library needs to be large in order to hide monotony or sameness in characters. For objects we’re less familiar with, like imaginary pink death birds, less variety is needed. To most people, most birds of the same species look the same. That’s true in animated films too.

Procedural animation means characters animate by randomly (or pseudorandomly) picking a sequence of generic animations from an animation library and blending them into one another. Such a library could hold actions, such as walking, fist pumping, playing with their bellybutton, turning and screaming, etc. The complexity of the library depends on the needs of the sequence. In the case of the swarming pink death birds, the sequence is frantic enough that I don’t think the animation library needed to be complex. A handful of flapping wings animations was probably sufficient. Freneticism hides simplicity.

Lastly, another challenge for crowds is intersecting geometry. By definition, a crowd means a lot of things sharing the same space in close proximity to one another. Since algorithms are randomly (or pseudorandomly) selecting animations for each character, it’s possible that geometry for one character could intersect the geometry of other nearby characters. Solid things in real life don’t pass through each other, so such behavior is generally undesirable in animated films.

One way to guard against intersecting geometry is to make the algorithms selecting animations for each crowd character more robust, so they can predict intersecting geometry before it happens and only choose “safe” animation cycles. Another option is to allow intersections to happen, but then correct them with collision detection and resolution algorithms.

Sometimes, intersecting geometry is tolerable. In the case of the swarming pink death birds, I suspect there’s a lot of intersecting geometry present that we simply don’t notice. The sequence is frantic, the cuts are short, and the birds are always in motion. We’re never given an opportunity to study the crowd, so we’re never given an opportunity to notice intersecting geometry if it’s present. I suspect the filmmakers didn’t spend resources fixing something that was likely to go unnoticed.

I’m sure a lot of work and care went into this crowd, but I think much more work and care would’ve been required had the sequence been paced slower. Regardless, it looks hard to do, so it makes my list.

Getting heavy. There’s a crane shot where the camera moves from the forest floor up through the forest canopy and high into the sky. I flagged this as hard to do because of the dynamic level of detail I assumed was happening behind the scenes. In computer graphics, level of detail refers to adjusting the complexity of geometry proportional to how close it is to the camera, more or less. Meaning, objects far away contain fewer vertices than objects nearby. Makes sense. There’s no reason to complicate your scene with things viewers will barely be able see. Level of detail helps keep load times and render times fast.

But what happens when a whole bunch of geometry starts a shot near the camera, remains in view for the entire length of the shot, and ends the shot far away from the camera? Tricky, right? You could just load in the heavy (lots of vertices) models and keep those same models in for the whole shot. But as the camera moves, a lot of other models come into view. Are all the models heavy? That’s probably not feasible. Dynamic level of detail could be an answer.

A man and his tiger. You know something you don’t see often in animated films? One character interacting with another character’s hair. Do you know why? I’m guessing it’s because it’s a hard thing to do. There’s a closeup shot in The Croods where Grug and a giant rainbow tiger cuddle in a cave. In that shot, you see Grug pet the tiger, and you see his hand interact with and deform hundreds of individual hairs. Did I mention it’s a closeup? The hairs fill the screen. That’s a lot of interacting simulations. It only takes one rogue hair to ruin the party.

A quick swim. Lastly, there are closeups of hero characters swimming in water at the end of the film. I don’t know a ton about fluid simulations, but I know reconstructing a water’s surface (which is probably being simulated with tens of thousands of individual particles) that’s interacting with complex geometry (like Eep) would be hard to do.

Epic notes

I performed a similar exercise while watching Epic before a Blue Sky interview. A lot of the hard things I noted in The Croods, I noted in Epic as well. Here are those notes truncated:

- Long tracking shots that cover a lot of virtual space.

- Characters interacting with foliage.

- Procedural effects (the rot). Procedural surfaces and materials (mostly everything, since the film takes place almost entirely in nature).

- Crowds. Lots of them. Procedural animation. Swarm behaviors. The rescue mission at the Boggans’ lair. The finale with the bats blocking out the moon. The army of Leafmen riding hummingbirds to go fight the bats blocking out the moon.

- Dynamic level of detail when the camera moves from a macro view of the forest to a micro view (and vice versa) in a single shot, which happens a few times since Epic is about tiny humans sharing a world with not-so-tiny humans.

- Realistic human characters. Epic was Blue Sky’s first film to feature realistic human protagonists. If the hair was “off”, viewers would notice immediately since we all know intrinsically what human hair is supposed to look like. Most people probably wouldn’t be able to point to the offending geometry or simulation, but they’d know something didn’t feel right. Same with clothing. Same with subsurface scattering and other reflectance properties of the skin.

How would you debug a black image?

Another common test in graphics interviews is to debug a given image. Maybe the image is noisy. Why is the image noisy? Maybe the reflections on a teapot don’t look quite right. What’s wrong with them? Maybe there are random hot spots in the image that are brighter than the rest of the image. What could have gone wrong in the rendering process to make those hot spots appear? Maybe the image is completely black. When you get a completely black image back from the render farm, what are some things you should test for to solve the problem?

I like the black image question. Maybe you forgot to put lights in your scene. Maybe your light linking is screwed up, so you have lights, but none of them are interacting with your geometry. Maybe your camera’s view frustum is too small, so non of your geometry exists in the camera’s viewable volume. Maybe your geometry normals are inverted, so rays are bouncing inside closed geometry instead of reflecting toward the lights. There are dozens of answers you could give. This is a good one to practice.

You have to ask your interviewers questions

This has been written about to death, but you need to ask your interviewers questions when given the opportunity at the end of your interview to do so. Always. It proves you’re interested in the position. It also gives you more information to work with when choosing which company you most want to work for. If you really can’t think of any questions you want answered, then you’re probably not interested in the job you’re interviewing for.

Here are some of the questions I wrote down before my interview.

One. By what date do you expect to make your hiring decisions for this internship position?

Two. Is housing for interns provided? (Answer: No.) If housing is not provided, does the studio assist interns in locating housing for the summer? (Answer: Not really.)

Three. As a technical director, how many hours per week do you work on average? How does crunch time affect your schedule?

Four. On average, how much of your day do you devote to development tasks vs. support tasks?

Five. Why did you choose to work at DreamWorks as opposed to another animation studio?

Six. Have DreamWorks’ recent expansions into content outside feature film production–specifically, its Netflix deal and its AwesomenessTV YouTube channel–changed the studio culture in any meaningful ways? (This question proves to my interviewers that I spent five minutes Googling the company before my interview. More people than you think walk into interviews without doing any research. Five minutes is all it takes to set you apart.)

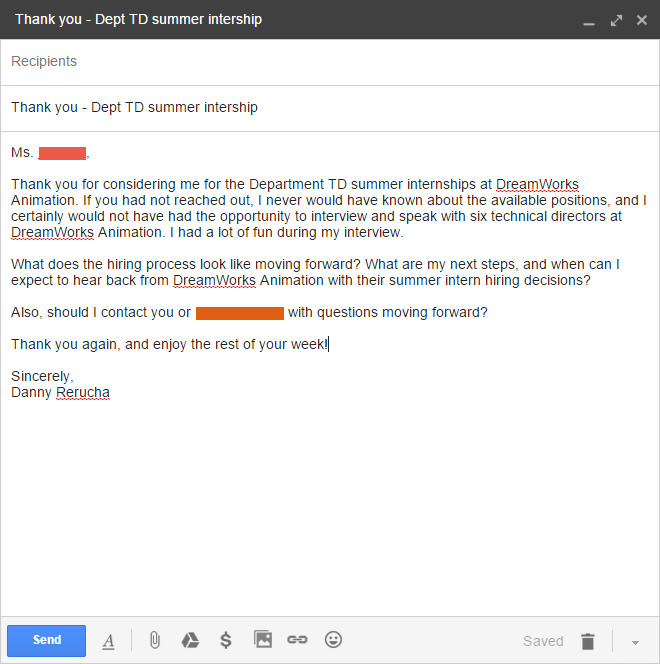

You have to send your interviewers thank you emails

This is also not optional if you want to make the best impression. It’s okay to use a template, but don’t send multiple interviewers identical emails. Assume they talk to each other. If you don’t know and can’t find email addresses, ask your recruiter!

I used a template. I met with 6 people in 90 minutes. Writing 6 heartfelt emails from scratch would’ve taken me longer than my interview did.

Here’s the template I wrote.

And here are two examples of how I personalized my template for different interviewers. The trick to personalization is to remember one specific detail about each interviewer. One thing is all you need. You’ll be surprised how quickly these details leave your brain though, so be sure to write them down as soon as your interview ends.

And of course, you need to thank your recruiters too. Here’s what those emails looked like for me.

In conclusion

Interviews are hard, but there are things you can do to make them easier. I hope you find some of the things I’ve done useful.

Oh, and I got the internship.

Cheers.

***

Image credit: Ahmadreza Sajadi

Hi!

This and your previous interview post were very helpful for me! :)

I applied for a TD internship at Pixar. Let’s see if I’ll get an interview and how I’ll do if I do get one… ^^’

Nevertheless, this was an awesome post! :)

This was pretty insightful. I’ve built an animation company in Botswana called Share Me Studio, and getting the right team members has and will continue to be a priority. With this I have a better understanding of how more established animation companies do it.